'Dear White People': The Three Words That Divide

Let's set the record straight: 'Dear White People' articles only serve to get clicks and agitate: both of which do not bridge gaps, but instead lead to further division.

I like to think that we can all agree on this one thing: the Western world is seemingly more divisive, ideologically fraught, and polarized than ever.

So why do we — or in this case, why do self-proclaimed activists and educators feed into this division by penning ‘Dear White People' style essays that do nothing more than blame, patronize, and condemn white people as if they are a single monolith with the same lived experiences?

After a few weeks of seeing a significant influx of ‘Dear White People’ style articles, out of curiosity, I did a cursory search online to see how far back this trend started. I found pages and pages of ‘Dear White People’ style articles dating back years on one website alone.

These are just some of the titles I found (all of which are on Medium—a popular blogging platform):

- Dear White People…Enough Is Enough

- Dear White Allies: Don’t Appropriate Our Anger

- Dear White Writers, “White Supremacy” is Not a Label and You Don’t Have a Clue How White You Are When You Make Black Writers Feel Blacker Than They Already Do

- Dear White Men: Your Defense of Whiteness is Astounding

- Dear White Protestors, You Are Not “Supporting” Black People in Their Fight

- Dear White Women married to Black Men, we didn’t give you a Black Card.

- Dear White People Your Privilege Is Killing Us

- Dear white people, I don’t like educating you about racism

- Dear White Women If You Want To Be “Allies” Just Say You’re Sorry

- Dear White People: Please Don’t Forget Your Privilege

- Dear White America: You Should Be Angry

- Dear White Girls at Protests, Stop, You’re Embarrassing Us

- Dear White People who like to jump in PoCs mentions and share your well meaning yet ultimately inept and uninformed opinions about race…Don’t.

- Dear White Writers, If You’re Not Qualified to Write About Race..Forget about it!

There are countless other ‘Dear White People’ articles across the web.

I include these headlines for a couple reasons. One, to show how far we have gone to sow divisions. Two, to show that even these writers disagree with each other on how racial justice should be tackled.

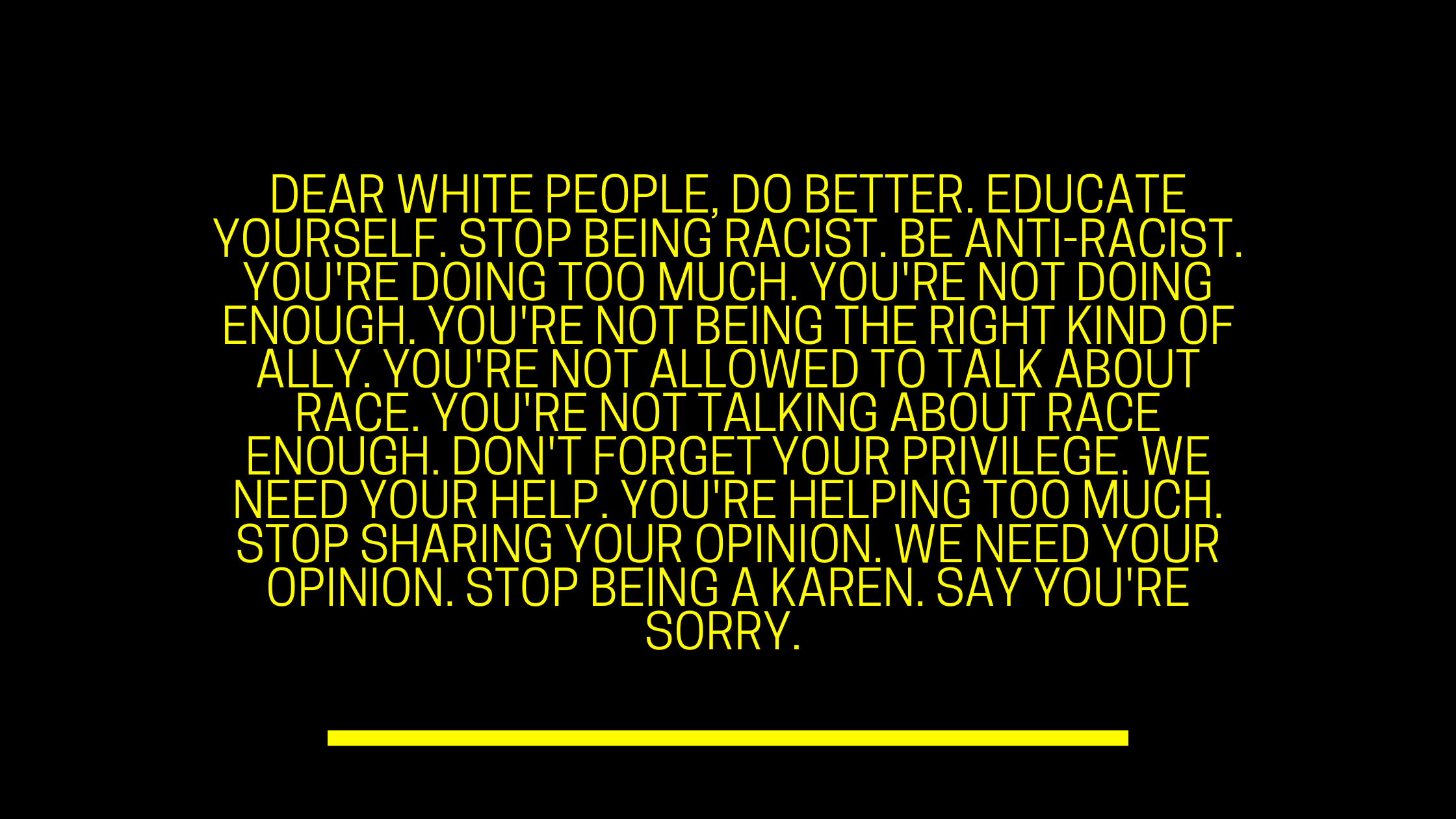

There’s a similar formula to all of these articles: the author writes at length about how white people are bad at x — telling them what they are doing wrong, then in the same breath, tells white people it’s not their job to educate them, despite writing an entire article addressed to white people. Then, if white people ask questions, they are mocked and ridiculed.

Everyone has an opinion. And when it comes to social justice issues, anything goes. Or rather, anything goes if the white person is on the receiving end of the blame. Condemning the white monolith is so in vogue that you won’t be cancelled or criticized by espousing hate and condemnation of an entire swath of people on the basis of their whiteness. If anything, you will be lauded for helping white people seek penance for their sins. All you have to do is write a scathing piece tearing down all white people. There’s no nuance, no class-based analysis, no acknowledgment of ethnic differences, and so on. All white people are either doing too much or not doing enough; they’re too vocal or not vocal enough; too guilty, or not guilty enough.

I don’t expect to see much compassion or attempt at nuance in a ‘Dear White People’ article because that’s not the point of them — most of us know it, yet we still read them. Guilty as charged. It’s a strategic move done on the basis of what will get the most clicks, not on sincerely inviting discourse. There’s no consequence for writing such an article because people who criticize them are — ding-ding-ding — accused of being racist. And nobody wants to fall into that trap.

Unfortunately, this divisive tactic works. But it didn’t used to be this way.

Years ago, when I started learning about these issues, I was first introduced to Peggy McIntosh’s essay ‘Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.’ It’s an oldie but a goodie. Written in 1988, the essay covers 50 examples, from Peggy’s perspective, on the privilege white people may experience in daily life. You can access the free PDF here. It’s still widely used today in conversations about privilege and oppression. The purpose of the essay is not to shame, blame, or guilt anyone. Peggy explicitly states this. Rather, the essay is about observing oppression on a personal and systemic level.

Additionally, the essay is not about generalizing the experience of all white people — it’s about starting a conversation based on McIntosh’s personal experiences. Peggy also specifically points out that getting trapped in definitions of privilege and power is dangerous as it lacks nuance and flexibility. She was all too aware of the dangers of polarity even decades ago. It is a great contrast from the anti-racist rhetoric that is so popular today, which works to compel, shame, and vilify the perceived oppressors, including anyone that expresses mild disagreement.

This was the kind of education I was surrounded by. In activist circles, I saw a great deal of compassion, kindness, and a yearning to understand from all parties. The goal wasn’t to compete for who was the most oppressed, but instead to acknowledge our differences, amicably disagree, and have an open conversation. And I'm afraid that even 'having an open conversation' is far too much to ask.

But some people are trying.

Take Professor Loretta J. Ross. Professor Ross is pushing back against call-out culture in one of her popular courses, 'Calling in the Calling out Culture,' at Smith College. Instead of blasting wrongdoers online, telling them to 'do better,' or worse, doxing someone for disagreeing, Professor Ross teaches students how to 'call in' people, and offers a number of practical solutions, including: sending a private message, calling someone over the phone, or even simply taking a breath (or two) before sending that scathing call-out post.

Hard to believe we need a course for common sense, but here we are. Like McIntosh 32 years ago, Ross is urging us to transform the way we have conversations by re-introducing a ‘compassion of culture’ into discourse.

But a compassion of culture is hard to nurture when we are constantly bombarded with these essays – they completely remove any possibility for discussion. They don’t serve to bridge gaps, only to satisfy clicks. And when you write for the sole purpose of agitation, a headline that reads 'Dear White People: Do Better' will always win out over a headline that reads 'How To Respectfully Disagree.'

And that is where we’re at today. We talk down to each other. We treat entire groups of people as if they are one and the same. We walk on eggshells and self-censor. And then we expect these same groups of people to apologize, ask for forgiveness, and educate themselves without asking any questions or seeking any clarification. We tell people to do better and come back when they have done good enough by some arbitrary standard set by a complete stranger.

This is a hot-button issue, and surely it will invite its fair share of criticism, but at a time when open discourse is sorely lacking, I encourage and welcome good faith discussions. It doesn’t seem possible with everyone talking down to each other, but I hope we can once again get to a point where people can make space and listen to each other. One can hope.

Featured image: Created in Canva

Support ad-free, reader-funded independent commentary

Become a monthly supporter:

Can't do monthly? Make a one-time payment via PayPal: