‘I Love Humanity, It's People I Can't Stand’

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s perennial novels are inundated with complex characters — they are often conflicted, multifaceted people who all of us can relate to in different ways.

In Crime and Punishment (1866), Dostoyevsky’s character, Raskolnikov, is mentally tortured and morally conflicted. He is simultaneously humble yet arrogant. He is riddled with anxiety and depression – his mental afflictions follow him everywhere. Raskolnikov made a lasting impression on readers; each of his traits resonate with each reader in a different way. In The Idiot (1869), Prince Myshkin, is the purest of all beings. Prince Myshkin exudes love, warmth and an alarming sense of naivety. He represents Christian purity in human form. His guilelessness has led to his reputation as “The Idiot.” Alyosha, from The Brothers Karamazov (1879) is an ethical, kind, sensitive soul – the complete opposite of his brothers. He is an advocate for justice and is deeply committed to his faith.

Through his characters, Dostoyevsky has gifted us with great insights and questions into the complexities and nuances of human nature and the exploration of broader themes of morality, religion, and philosophy – All of Life’s Greatest Questions are explored unwaveringly.

There are countless highlight-able passages, tidbits of wisdom, and seamless in-depth quotes on philosophy, society and culture scattered throughout Dostoyevsky’s books, like Easter eggs waiting to be discovered.

One of these quotes has later been popularized in contemporary society – though its origins remained a mystery – until now.

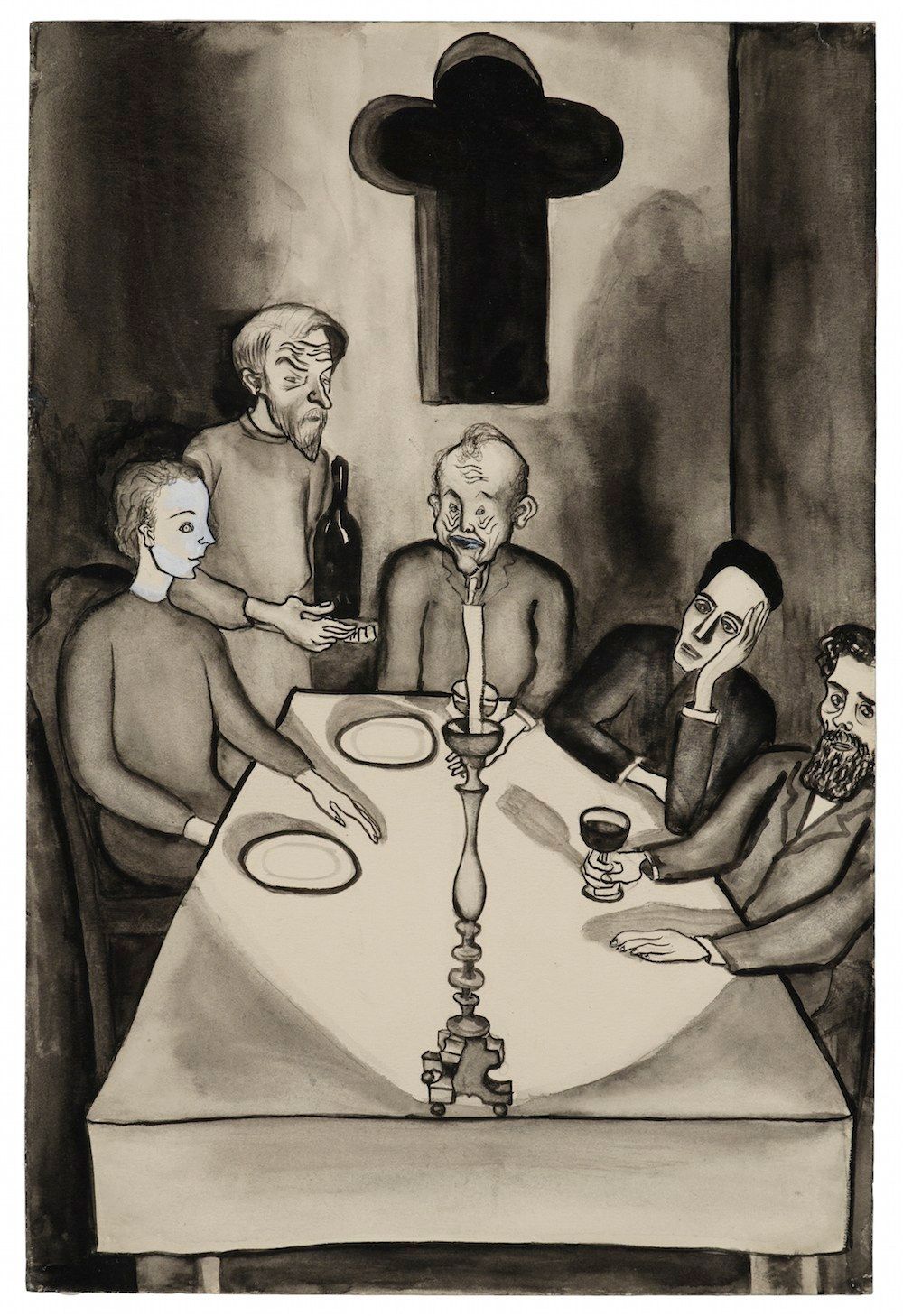

The below passage is an excerpt taken from The Brothers Karamazov (read in its entirety):

“I love humanity . . . but I can’t help being surprised at myself: the more I love humanity in general, the less I love men in particular, I mean, separately, as separate individuals. In my dreams . . . I am very often passionately determined to save humanity, and I might quite likely have sacrificed my life for my fellow-creatures, if for some reason it has been suddenly demanded of me, and yet I’m quite incapable of living with anyone in one room for two days together, and I know that from experience. As soon as anyone comes close to me, his personality begins to oppress my vanity and restrict my freedom. I’m capable of hating the best men in twenty-four hours: one because he sits too long over his dinner, another because he has a cold in the head and keeps blowing his nose. But, on the other hand, it invariably happened that the more I hated men individually, the more ardent became my love for humanity at large.”

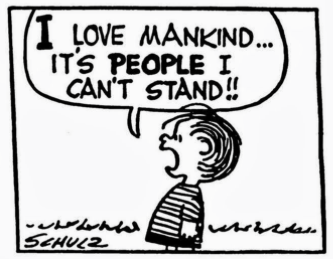

This excerpt was later poked and prodded and turned into this frequently revised iteration that we know today: “I love humanity, it’s people I can’t stand.”

Albert Einstein is one of the many thinkers whom the mediasphere (i.e. the internet) blindly attributed the aphorism. Like many other famous figures, there is a tendency to attribute a well known, but mysterious quote, to an equally well known figure. A quick online search pulls up a number of sites attributing the quote to Einstein, complete with fancy fonts overlaid on top of aesthetically appealing images. Pretty writing and images seem to lend the quote more credence online.

Marilyn Monroe is perhaps the greatest example of this. The Marilyn Monroe quote attribution is a common online phenomenon, where one site spreads misinformation and other websites re-publish the information without double checking the source. After that it spreads like wildfire, confirming the theory that 80% of online content is recycled garbage.

Still others believe the quote was coined by Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and playwright, Edna St. Vincent Millay. In Edna’s play Aria da Capo (1920), the character Pierrot was quoted as saying, “I love humanity; but I hate people!”

Aria da Capo is a political allegory; its literal translation is “air again” which describes an “operatice aria in three sections with the first and third sections alike and the middle section contrasting.”

And then came Charles M. Schulz. The modern day version of this quote appeared in Schulz’s infamously cynical comic strip, printed on November 12, 1959.

It is the mid-20th century revision of a quote describing man’s feelings towards one another.

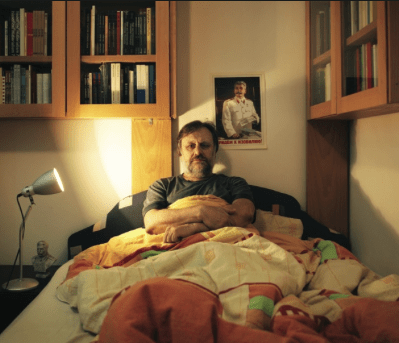

Slovenian philosopher and cultural critic, Slavoj Zizek puts his own spin on the quote, “Humanity is OK, but 99% of people are boring idiots.”

Humans have their own idiosyncrasies, quirks, personalities, neuroses, and egos. Dostoyevsky’s passage points out the humanness in men – “one because he sits too long over his dinner, another because has a cold in the head and keeps blowing his nose.” Individually, humans are unremarkable, yet capable of doing irreversible damage to themselves, others, and the planet. Individually, they are selfish, dumb, boring, egotistical, greedy. They are the bearer of every day annoyances: they poison ocean waters, they torture and kill animals every day; they cheat, they lie, they steal. People are easy to judge, blame, disparage.

But humanity – humanity removes all of these garish idiosyncrasies. Humanity is the summation of all people – it doesn’t have a face, but a collective sense of self. When we think of humanity, we think of compassion, kindness, goodness and understanding. Humanity as a whole is an abstract, it represents a societal ideal, it is blameless and faceless. Humanity has the ability to move us forward, to create positive change, to respect, to unite.

This post is for those who have long wondered about the origins of this oft-used quote. As of this writing we can conclude with confidence that the quote originated from none other than Dostoyevsky – well before Einstein, Millay, and Zizek. (That is, until someone else comes along and corrects us). Regardless of who and when, this timeless quote will continue to outlast us and I’m quite pleased to know that Dostoyevsky has had such a profound effect and influence on the English language — even to this day — despite him not being properly acknowledged for it.

This piece first appeared on the personal blog of Growing up Alienated in March 2019

Featured image credit: The Brothers Karamazov illustration by Expressionist Painter Alice Neel (1938)

Become a monthly subscriber

Become a Patron!Donate via PayPal